Braced up by this new data, he goes into full private investigator mode (a la Chinatown) in uncovering the truth of “The Twenty Days”, wherever it may lead.Īt the time, when these murders and the “phenomenon of collective psychosis” were visited upon Turin, the institution known as the “Library” came into existence as well. “The bas-reliefs? Oh, I can’t remember well…He said that they were badly worn out…He seemed to recognize images of himself as a child and the faces of our mother and father…” Our inquisitive narrator leaves this meeting with unique information concerning the death of Bergesio. This Millenarist recounts her brother’s disturbing dream (whenever he was able to fitfully doze off) just prior to his death of a dried-out lake with a very deep bottom. To make matters worse, during that late, draught inflicted spring (and early summer), these somnambulists began dying in a highly gruesome and bizarre manner.Īt the onset, our narrator is interviewing the first victim’s, Giovanni Bergesio’s sister, Alda. A decade previously, a wave of mass insomnia plagued the city, in which, droves of sleepless citizens milled about aimlessly in the various piazzas. This man’s eventual goal is to write a book on the phenomenon, collectively known as “The Twenty Days of Turin”.

A nameless narrator (a salary-man by trade) and denizen of the city is in the process of investigating the strange circumstances that took place a decade earlier. The Twenty Days of Turin takes place on the verge of the 21 st Century, in that “City of Black Magic”.

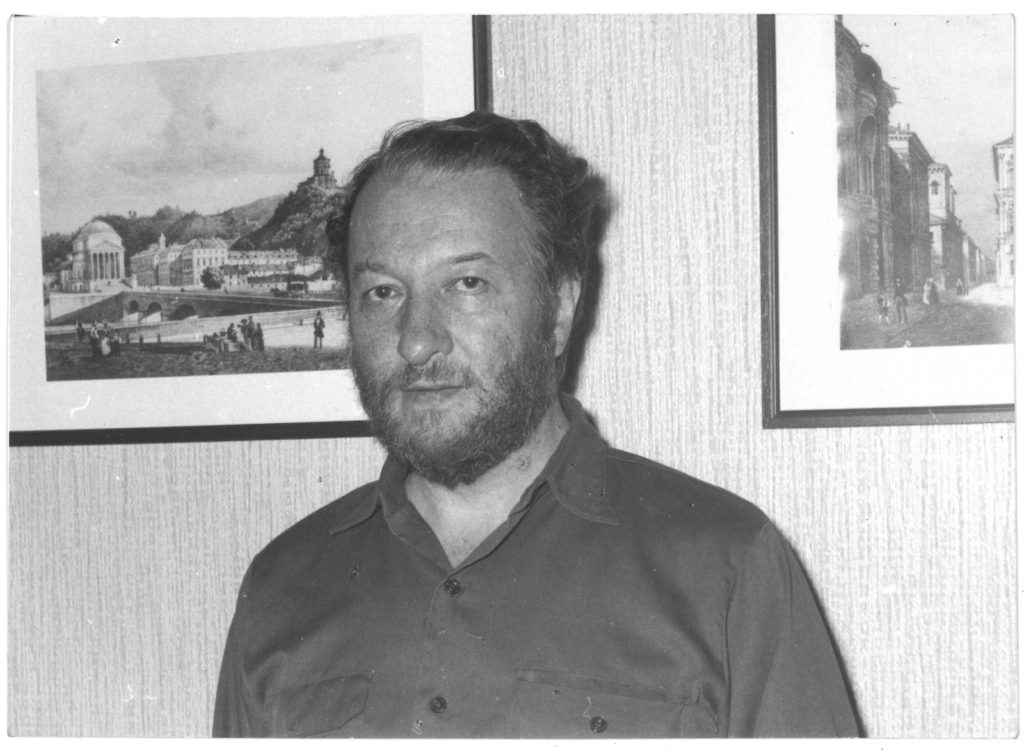

Or as Roman Glazov states so eloquently in his Translators Introduction “Like Maistre before him, De Maria imagined a Divine Providence that was ruthless, opaque and, viewed through limited human eyes, seemingly amoral…The only safe choice available is not to pry too deeply.” The Twenty Days of Turin examines the phenomenon of political strife and violence through the pessimistic lens of cosmic horror. But unlike those two companions, Giorgio De Maria explored topical political concerns in a profoundly different way. De Maria ran in the same circles as the luminaries Italo Calvino and Umberto Eco (they were members of an avant-garde music group, ‘Cantacronache’, that sought to dust off and politicize traditional Italian folk songs). This back and forth conflict between (as a simplification) left and right-wing factions, took a great toll on the citizenry of Turin and well beyond. This turbulent era lasted from 1969, well into the 1980s.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)